Learn from Qatar / Swalif: Qatari Art between Memory and Modernity

This article itself is an introduction to my own attempt to "learn from Qatar." Learning in this sense is not a "looking back" or "looking down," so much as it is a looking across, an opening to a conversation. The hope is to turn away from the hierarchical discourse of tradition and modernity, and towards the humility of dialogue. One of the main themes of this attempt will be conversation itself with a look at the exhibit, "Swalif: Qatari Art between Memory and Modernity." (Swalif itself is an Arabic word that "suggests friendly, informal conversations and stories.") I will also be exploring modern and contemporary art from the region more generally, as well as those architects whose visions have been one of learning from Qatar, such as I.M. Pei and Jean Nouvel. (Given that Pei was one of the architects originally criticized by Venturi, Brown and Izenour, it is worth seeing how his modernist vision has changed over time!) As I approach these works, I will do so with the humble, conversational engagement that allows for learning as a reciprocal adventure.

Over the past decade, a remarkably complex discussion of modernity and the Arab world has occurred side by side with the various diatribes about a "clash of civilizations" or the "backwards Arab mind." While authors of the latter camp have insisted that a victory must be achieved by either the Arab world or the modern West, more nuanced discussions have focused on how cross-cultural learning can call into question the assumptions and life choices of all peoples. For example, Pakistani-born, U.S.-based anthropologist Saba Mahmood has written that her work with women in Islamist movements in Egypt led her to question the secular leftist values she had so long championed and lived by: "In short, it has compelled me to leave open the possibility that my analysis may come to complicate the vision of human flourishing [secular-left politics] that I hold most dear, and which has provided the bedrock of my personal existence." Mahmood stands by her commitments to various forms of equality, but she no longer insists that the politics and religious views of the modern West form the necessary grounding of those politics. Mahmood stands in a tradition of thinkers including al-Biruni, Montaigne and Rousseau who found in other ways of life not simply oddities to be studied, but truthful modes of being that called into question one's own settled attitudes. Such is the route taken by many modern artists, regardless of their geographic origin. Modernism as an injunction to, in Ezra Pound's phrase, always "make it new," requires an imagination that is restless with inherited forms and habits. Indeed it is well documented that much of so-called Western modernism drew its influences from global cultures – from the African and Cambodian masks that influenced Picasso and Modigliani to the abstract and geometric patterns from Islamic art that influenced the work of Klee and Matisse. This documentation itself – and the controversial meaning of it – has not been merely done in European or American universities. As Nada M. Shabout points out in Modern Arab Art, there is a long-standing discussion in Arabic scholarship in the writings of Afif Bahnassi, As ̔ ad Orabi and others about such issues. But as Talal Asad reminds us in his important work Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, the volatility of the category "modern" does not remove its political significance: "The important question, therefore, is not to determine why the idea of 'modernity' (or 'the West') is a misdescription, but why it has become hegemonic as a political goal, what practical consequences follow from that hegemony and what social conditions maintain it." This, too, is equally true of modern art. The fact that "modernism" is not an entirely Western phenomenon, does not erase the fact that non-Western artists are often placed in one of two strictures: either to capitalize on their ethnic status and present 'traditional' works for tourist consumption, or modernize their work to appeal to an international audience. Like a Procrustean bed, modern art forces people either to stretch to conform to certain standards, or to cut off the excess of their actual condition in order to remain "pure." This problem is to a large extent generated by how we conceive of the relation between tradition and modernity.

photos by Jan De Cock

Contrary to standard accounts, tradition and modernity do not confront each other. Tradition exists, and modernity exists. They interact as does a grandfather and his grandson: the older is changed by the younger, as the younger is changed by the older. Each rebels, in his own way. Each is entrenched, in his own way. The path out of the bind is not accusations, and, as Asad argues, it is not mere redescriptions. The path out rather is conversation, in its etymological sense of con and verso: turning with. Tradition and modernity turn with each other, to face the past, the present, and the future. And since the past cannot be fully cognized, the future never fully known, and the present never fixed and stabilized, each turns with humility, and with recognition of the other's point of view. Such was the project, from the start, of that great break with the doxas of modernism, Venturi, Brown and Izenour's Learning from Las Vegas. In their respect for the "vernacular," these authors and their students had a conversation with the architectural layout of a city. They accepted it on its own terms while at the same time bringing classical and contemporary methods of analysis to bear on it. Rather than an imposition of form, or a gleeful celebration of complexity, they simply asked what, without judgment, it might mean to understand Las Vegas on its own terms: "There is a perversity in the learning process: We look backward at history and tradition to go forward; we can also look downward to go upward. And with-holding judgment may be used as a tool to make later judgment more sensitive. This is a way of learning from everything." This article itself is an introduction to my own attempt to "learn from Qatar." Learning in this sense is not a "looking back" or "looking down," so much as it is a looking across, an opening to a conversation. The hope is to turn away from the hierarchical discourse of tradition and modernity, and towards the humility of dialogue. One of the main themes of this attempt will be conversation itself with a look at the exhibit, "Swalif: Qatari Art between Memory and Modernity." (Swalif itself is an Arabic word that "suggests friendly, informal conversations and stories.") I will also be exploring modern and contemporary art from the region more generally, as well as those architects whose visions have been one of learning from Qatar, such as I.M. Pei and Jean Nouvel. (Given that Pei was one of the architects originally criticized by Venturi, Brown and Izenour, it is worth seeing how his modernist vision has changed over time!) As I approach these works, I will do so with the humble, conversational engagement that allows for learning as a reciprocal adventure.

Artificial dune and the Zigzag Towers photo by Jan De Cock

The first icons form Doha

“Most of what passes for urban and city planning in the broadest sense has been infected (some would prefer “inspired”) by utopian modes of thought.” — David Harvey

Until the 80s, the countries and independent sheikdoms in the Persian gulf region had no architecture of reknown. This was certainly the case for Qatar, as even the Lonely Planet called the capital, Doha, the “dullest place on earth.” Qatar started from its independence on (in 1971) - like its neighboring countries- to reshape the landscape. Fast changes in architecture as well in urban development and the decision to invite international architects (for the ruling family and educational, cultural and urban reasons) led after a long period of tradition to Qatar’s unique modern architecture. Keep in mind that until not so long ago, the peninsula on which Qatar rests was populated almost exclusively by Bedouin nomads. It has grown this modern culture, education, politics and society only recently. What makes its modernization unique is that it has also incorporated many elements of its nomadic and anti-colonial past into the modern. As such, they have tried to find a balance between new necessities, modernity and their traditional architecture.

Right after their independence, ministries were built, but the only significant project realized was the conversion of the Emir's palace (1918), into the national museum, by the architect Michael Rice & Co (completed1977). The project got the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in1980. The jury stated: "in a period of rapid social and economic change, when the widespread and indiscriminate destruction of the architectural heritage has broken all continuity with the past, the preservation, enhancement and adaptation to a new public use of this important group is a noteworthy achievement."

But it is still not until 1980 when some major projects were completed. , Until the mid 70s, architecture in Doha remained mostly an architecture of tradition, which was generally the case in the whole gulf region. But from then on it’s been a time of modernization, or, as Khaled Adham writes, from '72 to '84 it became an “urbanity of modernization.” This was the time before the skyscrapers, the time of many possibilities, and also a time when the population of expats and locals was roughly aligned . Today, more then a quarter-century later, we can review the proceeds and see which projects survived in a place that has been constantly changing, building, and rebuilding. In a city that is still in a (almost schizophrenic) struggle between hunger for the new and a search for its roots. Which are the projects that helped shape the country and give it an identity? Which are the ones that survived the rate of change?

photos by Jan De Cock

Many planning teams (teams consisting of a range of disciplines including architects, landscape designers, economists and anthropologists) were invited from the UK after the independence. This was a period when city planning was seen as a more practical process. In the beginning master planners such as Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker and Bor to Peat Marwick Mitchell and Company that carried out the Traffic and Transportation Master Plan were invited. Many other consultant planners followed and were brought to advise the government for planning development. Due the involvement of different government agencies it became rather difficult to carry out the specifics of the plans as they were proposed. Most of them wound up as adaptations of initial proposals and were developed from a Western perspective. In this place where everything could be built from scratch, where they seemingly had the space, knowledge and money to realize any plan, still nobody got the actual opportunity to plan a city like Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer got in Brasilia (1956-1960), or Athenian Constantinos Doxiadis, planner of Islamabad (1959-63) nor like Le Corbusier had in Chandigarh (1951-1965). At one point there was a possibility to carry out a major urban development project when the Los Angeles-based William Pereira (1909-1985) was brought to Qatar and hired in 1973 to shape Doha Bay. The architect was known for his futuristic, science fictional and often brutalist style buildings such as the Transamerica Tower Pyramid in San Francisco (1973), the UFO-like LAX theme building (with Charles Luckman, part of his Los Angeles International Airport master plan 1967-1984) and the University of California Central library, San Diego (1965). Besides such buildings he also designed movie theaters and the studios for Paramount, where he later became art director.

Pereira got the task to plan the development of the new district of Doha . He studied the existing radial pattern structure of urban development and changed it to a linear pattern to make it more open to expansion. The government also decided to locate some of his remarkable projects along the access road, including a five star Sheraton hotel and other commercial and leisure developments.

But mainly Pereira's projects remained undeveloped, in large part because of the drop in the oil prices in the early eighties. The Sheraton and additional conference centre was the only project that was realized and finished in 1982 from Pereira’s original plan at the edge of the Corniche and the New District of Doha. He said of his interests as an architect: …“It is this appetite to accommodate the future that puts my ear to the ground to shut out today’s racket in order to hear the footsteps of the future.” His fascination with science fiction was dominant in structure of the Sheraton. At that time it looked formally almost like a pyramidal spaceship that had landed in the desert.

William Pereira, Rear facade of the Sheraton hotel, 1984-1985 and Conference hall

- photos by Jan De Cock

Pereira effectively combined his ideas from science fiction together with local elements. For example, with the recurrence of the triangle, he refers to the use of geometry in Islamitic architecture. This was the first major construction project using innovative and high standard building methods in Doha. The Sheraton became the new icon of the city and was seen as a combination of elements of their own culture combined with Western concepts. Inside the building the architect followed an Islamitic tradition of internal schemas that are open on themselves but closed on the outside world: a13 story atrium is a large, open meeting place, although it is totally closed and there is almost no view on the busy street outside. The hotel has 439 luxury guest rooms and suites, each of which has a private balcony. Because of the sloping side of the pyramid and concrete balustrades, there is no sightline in from the outside. The attached conference center includes a 750-seat auditorium and telecommunication services that make simultaneous translation in 7 languages possible. In spite of the ambitious contemporary architectural projects later built, the Sheraton remains until today the city's treasure and icon.

Soon after, other governmental buildings began to appear along the Corniche including the post office and other ministerial buildings. The post office was built by Comconsult from Cambridge (1980), and completed in 1985. It is somewhat a more baroque version of the pyramid-like structured Sheraton. The post office grabs one's attention through its uncanny outer design: a façade that is covered with tube end-like structures and a large structure that included multi-story car parking.

Comconsult, detail post office, 1980 -1985

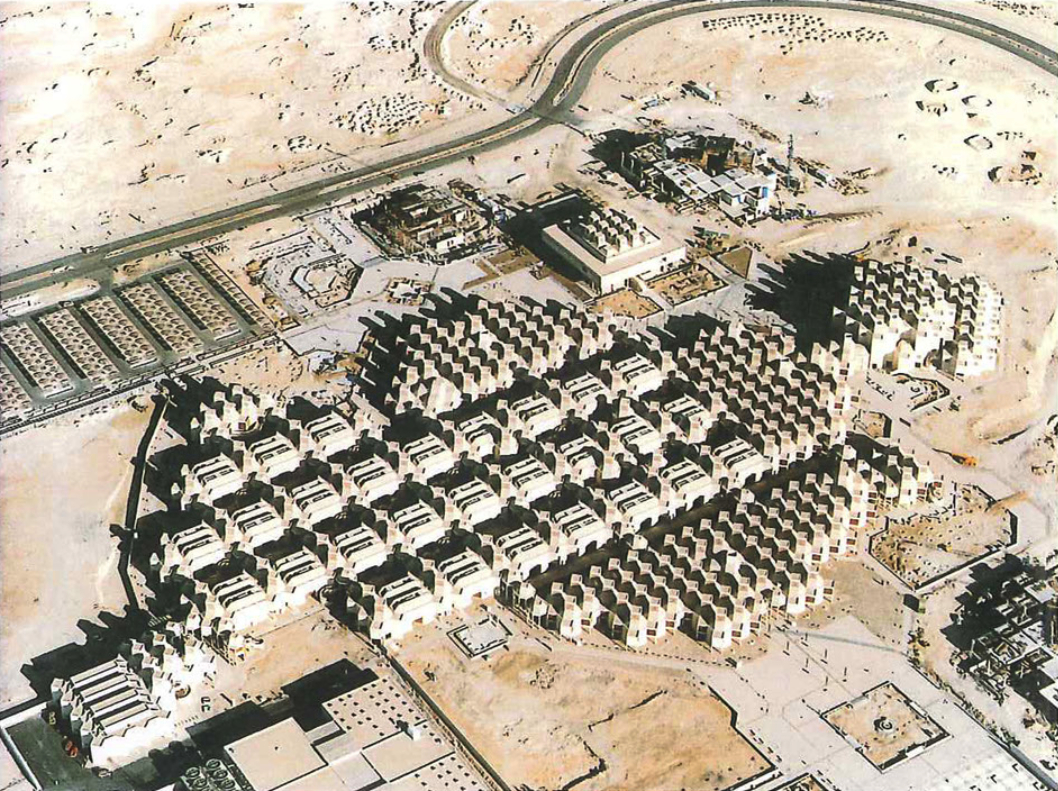

A building that spanned in time over these projects and takes more then a decade to complete is the new University of Qatar (1973-85). This building took to another level the demand to find a balance between the traditional architecture and contemporary ideas. Commissioned to the Egyptian architect Kamal El Kafrawi by UNESCO in 1973, the building was then called Gulf University. Planted on a hillside in the middle of the desert it needed to be a landmark. The low-rise buildings are concrete and modular, and are formed by the repetition of pre-cast elements (including concrete bearing walls, sloping pre-cast units for the roof structure arranged to interchange the octagonal plan into a square). The plan is based on two grids: one an octagon with a width of 8,4 m, and the other a square with sides of 3,5m. The university was needed so that the government could offer the possibility of Western education to local students without their leaving the country. In 1985, the first phase was completed: a civil engineering college and college for science. The colleges and several campus facilities are separated for men and women. Additional buildings include a mosque, main auditorium, library, cultural center, recreational facilities and staff housing.

This building is a feat in combining old techniques of the traditional Arab architecture together with new building techniques from the West in an honest way. Arabic traditional architecture and more specific traditional architecture from Doha were taken as model through such elements as windtower chimneys to create a natural ventilation system for cool air and reduced humidity. There are also light towers with mashrabiyyas, some in stained glass with colorful geometrical motifs, to temper the strong sunlight. The natural light, octagonal ground plan and partly covered courtyards protect the campus from the hot climate. That these exemplary modifications come from the Arab cultural tradition made the building another icon of Qatar. This low-rise site spans over an area of 2.500.000 square meters with a total floor space of 73.000 square meters. It is a masterwork of abstract geometrics in architecture.

Kamal El Kafrawi, aerial view University of Qatar, 1983 -1985

It’s worth mentioning that the plan of the Qatar Zoo (completed a bit earlier in 1983), also uses the idea of the grid. Here it is hexagonal rather than octagonal. For the zoo the architect John S. Bonington juxtaposed local desert stone for the building itself with a high tech metal roof covered with geometrical abstract figures, colored in green. The whole complex is covered by this roofwhich provides a shelter from the sun.

These buildings are representative of a period in time right before the real building fever struck. With a common angular, geometrical appearance and the use of repetition of geometrical forms, these buildings are reminiscent of strands of brutalist architecture. Thus although this movement flourished earlier around the world, perhaps this is more a refined version; perhaps a brutalism from the Gulf? Then, perhaps, this was the moment that modernity and tradition were in perfect balance. Even in a region where anything could be done, still there was no desire to return to the utopic models of the 60s.

sources:

http://www.learningfromqatar.net/en/documenters/angelique-campens

University of Qatar, 1983 -1985 - photo by Jan de Cock

Manifesto for an educational institution in the UAE as societal agent

Markus Miessen – December 2011

This institution...

Should be a localized, small-scale hub.

Should regularly perform cultural and educational activities in collaboration with local NGOs, schools, and individuals.

Should aim for a long-term local presence as a critical platform for exchange.

Should enact a non-preemptive, roaming, and non-consensual programme.

Should appreciate the value of failure.

Should institutionalize a frequent regime of “learning from” scenarios.

Should be a low-threshold space of knowledge (production).

Should question the default modes of institution building.

Should foster non-romantic forms of local engagement.

Should set itself apart from the US-model of franchised campuses.

Should generate local knowledge.

Should generate toolboxes that will remain within the region and are specific to the context in which they are situated.

Should be visible.

Should assume permanent local responsibility.

Should generate a turf for the concept and reality of consequence.

Should be a space for support.

Should be thought as a spatial typology for political exchange.

Should produce,

Should provide.

Should demand.

Should consume and exhaust.

Should be a non-profit space that accommodates an opposition, not in the sense of being “against” something, but a space, which is based on the notion of both political autonomy within the context in which it is situated as well as to put forward an autonomous institutional framework, which is deliberately introduced from the outside, yet embeds itself within the actors, realities and questions of local and regional practices.

Should allow for a decentered perspective of politics.

Should promote a sensitization towards everyday practice of the local and communal.

Should promote itself as a gathering space.

Should be a protected space for congregation.

Should assume the position of an uninvited outsider.

Should be based on a regime of hospitality yet opposing the myth of an open public space of participatory decision-making.

Should wear a strong directorial voice.

Should be a transparent civic institution.

Should become an agent through which political and other tensions can be channeled into more organized and productive forms and formats of discussion.

Should question both the normativity of the space of the “School” as well as the normativity of those communal spaces and practices.

Should be a Mouffian space in which one agrees to disagree.

Should be a space of oppositional but non-violent encounter.

Should stop making sense.

Should be a community in the making.

Should be a horizontally accessible space.

Should believe in spatial complexity.

Should entertain democratic pluralism.

Should be an agent of political contention and social change.

Should assist in un-learning the normative and default Western roles and educational models and conventions.

Should produce reciprocal links between the local and that, which is not.

Should assume limitless responsibility for its actions.

Should inhabit the consequences of its production.

Should attempt to maneuver between a diverse set of practices, relations and social networks.

Should be proactive, optimistic and energetic.

Should understand itself as a self-authorized enabler.

Should be based on an underlying principle of questions rather than answers.

Should introduce a destabilizing momentum.

Should contaminate the imagination of others.

Should perform itself as an autonomous agent, enacting and producing in relation to the given context and its specific audience producing affect.

Should instigate a zone for dissensus.

Should enable alternative formats or frameworks of production.

Should engage contingency.